19 Days in Myanmar

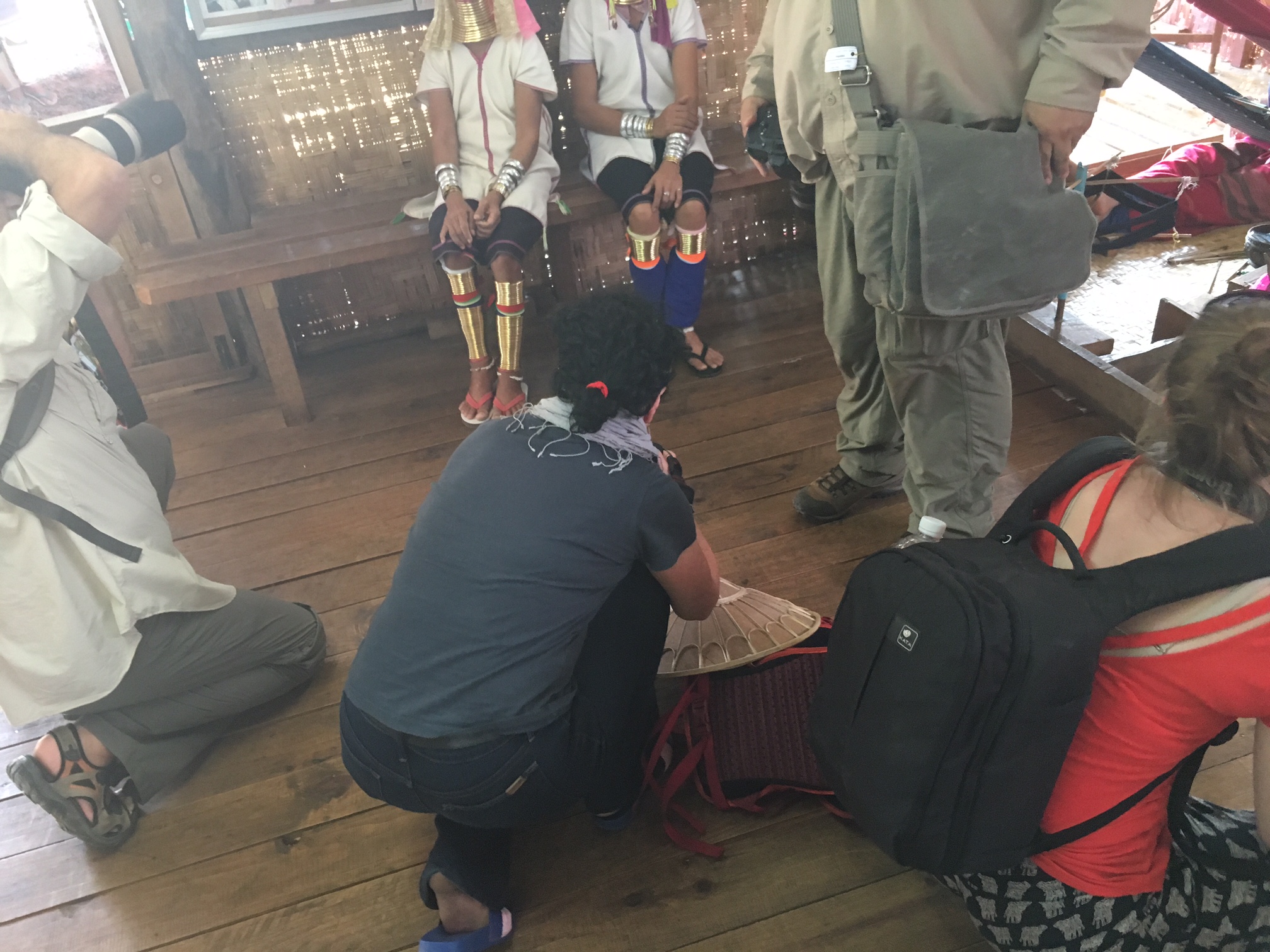

When our tour guide in Inle Lake took us to see the “longnecked” women—members of Myanmar’s Kayan ethnic group who wear brass rings around their necks, and who are often portrayed in tourist ads promoting Myanmar—I didn’t know what to expect. Instead of taking our long boat to a village, which is what I had anticipated, we pulled up to a souvenir shop on stilts over the water. A bit confused, Cole and I got out of the boat and pushed our way into the crowded store. Our guide tugged us through the pack, past piles of key chains and bracelets, past silk-and-lotus scarves and Myanmar cigars. There, on display at the back of the store like the other souvenirs, were the longnecked women. Some were weaving, while others simply sat and smiled for the dozen or so tourists who shoved cameras in their faces, jockeying for the spot that would allow for the best angle. Our guide encouraged us to take pictures, too, but we were instantly uncomfortable. Instead, we decided to capture this strange moment of tourists determinedly documenting Myanmar’s “traditional” culture. It made us uncomfortable, though it begs the question, is this inauthentic? The women are paid, which enables them to feed their families and support their villages. This also enables them to share a bit of their culture with tourists, who otherwise wouldn’t likely venture to their villages. On the other hand, despite their smiles, they couldn’t communicate with the people taking pictures of them. Did they feel like models or cultural ambassadors, or did they feel like zoo animals? Perhaps more importantly, are we really in a position to judge? I don’t know the answer to these questions, but they are hard to avoid in a country where tourism is so new and the country is changing so rapidly in response.

As Myanmar has opened up over the past few years, there’s been a fascinating cycle of change that both attracts and reacts to tourism. Cole and I spent almost three weeks in the country, which after decades of human rights violations, fighting, sanctions, and military rule—all of which led to the country’s isolation—has begun to stabilize over the last five-or-so years, enabling much greater engagement with the international community. There have been myriad advances over that period of time alone, some tangible (ATMs and access to banking; vast 3G networks and SIM cards that have dropped dramatically in price; hundreds of newly-built hotels and guest houses to accommodate the tourist boom), and others that buzz through the air like high voltage waves (sweeping optimism and giddiness surrounding the very recent election in which the National League for Democracy took a landslide victory, ending nearly 50 years of complete military rule). Every Burmese person we spoke with was absolutely thrilled about each one of these developments and the pace with which they have been emerging and changing. As an outsider, I’m more cautiously optimistic. For example, the rapid economic development is not without its cost; in its efforts to raise funds, the government has turned to monetizing Myanmar’s natural resources by selling them to China, mortgaging the country’s economic future. And while the election is a massive win for the people in Myanmar, it comes with some pretty limiting stipulations that the military baked into the new constitution in 2008. For example, the constitution can’t be changed without military approval, the military gets 25% of the seats in parliament, and the army also has the right to select significant security ministers.

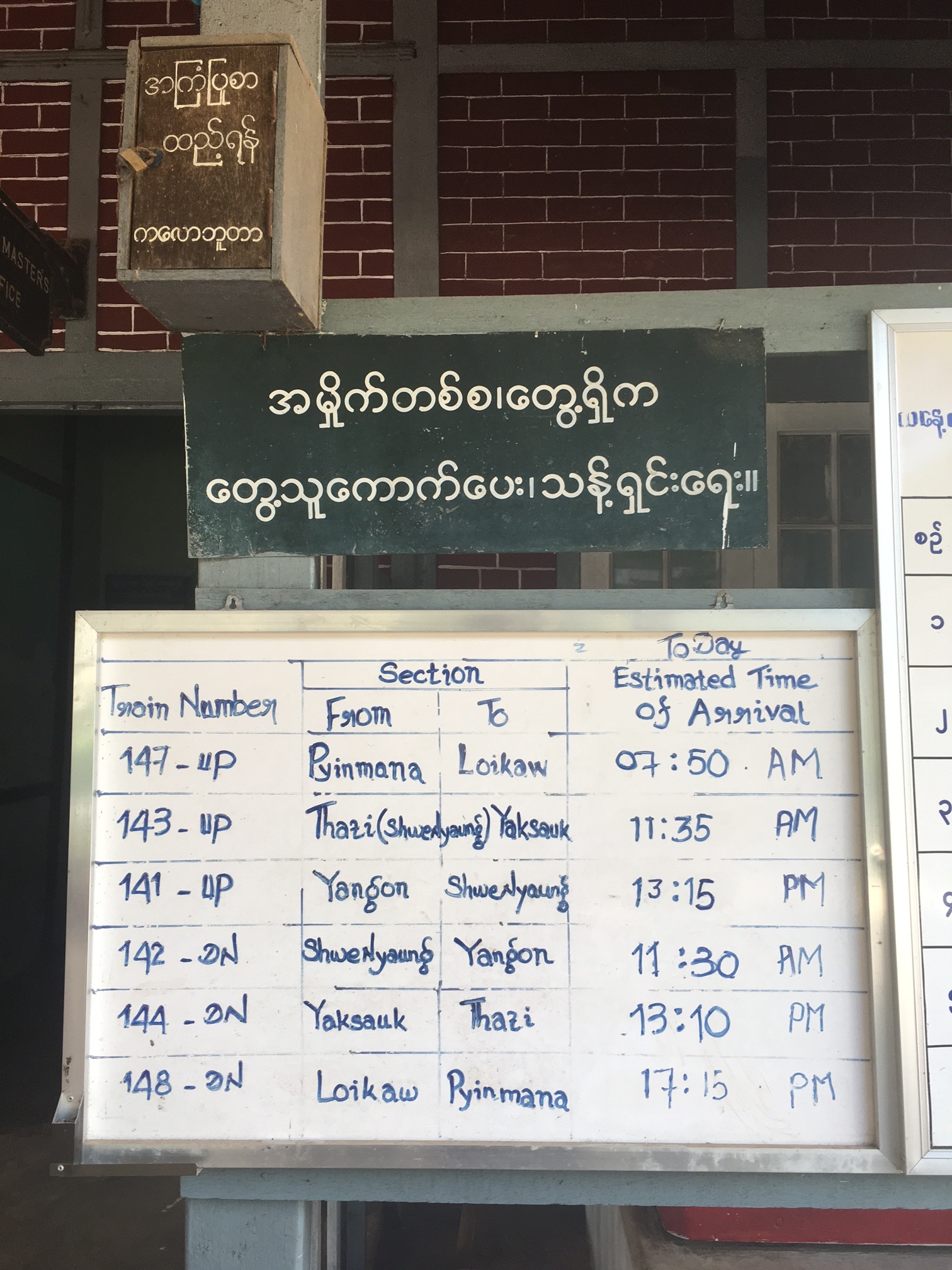

Inevitably, to travel in Myanmar is to observe this process of rapid change. As Myanmar has opened up, the country has been inundated with technology, imports, and pure newness—so much so that it’s all being adopted in bits, and with varying success, creating a patchwork of development. The haphazard chaos makes sense—I mean, how do you build a world of future technology when you lack basic infrastructure? The answer was clear as we made our way around the country: any way you can. On our two-night trek from Kalaw to Inle Lake, we passed through multiple villages. Some had 3G networks and power lines, while others relied entirely on solar panels to power their homes for small periods of time each day, and none had running water. In Yangon, where electricity is ubiquitous but goes out at least once per day, motley crews of men in flip flops and tank tops gathered in groups to hang power lines, stringing them like Christmas garland from pole to pole, which they climbed with a rickety step ladder. In Ngapali Beach, where there were no cell networks and abysmal WiFi, people were still using satellite phones instead of standard cell phones. Flight delays are communicated by pieces of paper taped to walls, and flight boarding is communicated by a man running around the terminal with the flight number written on a white board, frantically looking for people wearing a sticker that indicates their flight (yes, you have to wear a sticker that has your flight number written on it). Immigration records are written by hand, creating massive lines as airport officials scrawl passport and visa numbers into massive books.

Myanmar may be fumbling to find its stride amidst these developments, but the country is gritty and beautiful. And maybe it’s the newness of foreigners (multiple groups of domestic tourists wanted to take a picture with us, and a few asked our tour guide if we were movie stars!), or maybe it’s simply the Burmese culture, but the people we met were incredibly welcoming. The particular moment with the longnecked women described above was so uncomfortable because it felt like one-way observation, but most of our time in Myanmar didn’t have this feeling. Rather, the Burmese people were constantly reaching out, allowing us to tour the culture via these interactions in a way that was decidedly genuine. On our trek, farmers waved animatedly from ox-drawn plough carts and excitedly displayed newly harvested carrots. Kids sprinted after us as we walked through their villages to thrust flowers into our hands. At Inle, teachers allowed us tan impromptu visit to observe their 3rd grade class in action, reciting a Burmese poem in their building on stilts in the middle of the lake. In Bagan, women at the market painted my face with thanaka, a paste made from bark that Burmese women (and some men) wear both for beauty and to protect their faces from the sun.

There is no doubt that Myanmar will continue to evolve, but its people’s optimism and warmth will carry its character for years to come.

- Alex